What Part of the Brain Reads Words

Our brains are quite proficient at recognizing jumbled words and reading them correctly. Researchers from the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, studied this fascinating phenomenon and came up with a computational model that uses artificial neurons to simulate the style the encephalon processes jumbled words.

How does our brain read jumbled words correctly? Scientists led by SP Arun and M V Southward Hari from the Centre for Neuroscience, Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, have adult a computational model that sheds light on this. According to this model, when we see a string of letters, our encephalon uses the letter shapes to form an paradigm of the word and compares it with the closest visually similar give-and-take stored in our brain.

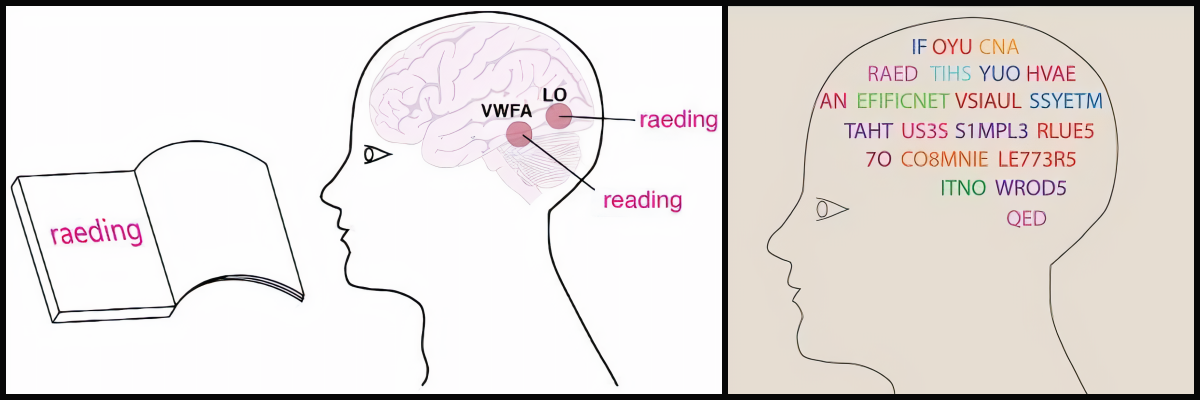

Reading words is a circuitous process in which our brain decodes the letters and symbols in the word (too chosen the orthographic code) to derive meaning. Earlier research has shown that our brain processes jumbled words at various levels — visual, phonological and linguistic.

At the visual level, information technology is easy to read a jumbled discussion correctly when the first and the final letters are retained and the other letters are jumbled or replaced with letters of similar shapes. Yet, some arrangements are easier to read than others. For instance, 'UNIEVRSITY' is easier to read than 'UTISERVNIY.' We can likewise read words when numbers of similar shape supervene upon letters, east.g. "7EX7__WI7H__NUM83R5."

At a linguistic level, information technology is easier to recognize words that we encounter more frequently or have frequently-used letters. At the phonological level, it is easier to recognize similar sounding words, east.yard. tar/motorcar, pun/fun etc. Still, how these factors contribute individually or collectively to recognize words remains unclear.

"We bear witness that our ability to read jumbled words comes from elementary rules in the visual system, whereby the response to a cord of letters is a weighted sum of its individual letters," Aakash Agarwal, first author of the paper, says.

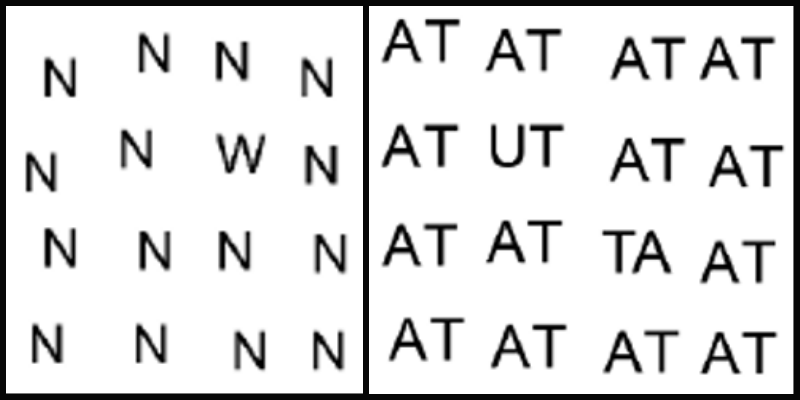

The squad asked fluent English speakers anile 22 – 27 years to search for the odd letter out within a grouping of letters (distractors) displayed on the screen. The researchers found that the more similar were the shapes of the odd letter and the distractors, the more fourth dimension the subjects took to accurately spot it. The team could thus summate an index of how like or different English messages were to each other, based on the time taken by the subjects to spot the odd letter in this experiment.

Using this information, the team proceeded to design computational units (artificial neurons) that were mathematically tuned to gauge how similar or dissimilar letters were to each other, thereby mimicking the neurons in the encephalon. Using these artificial neurons, the team so predicted how much time human subjects would take to identify odd ii-letter combinations hidden within an array of two-alphabetic character distractors and found that the predictions matched the experimental findings.

The researchers then tested the responses of the artificial neurons to four, five and 6-letter words, studying how hard or easy it was for these neurons to distinguish actual words from jumbled words. The more than similar the shape of the jumbled word was to the right word, the more difficult it was to identify it as jumbled. It was also more hard to spot jumbled words when the first and the last letters were kept the aforementioned. For example, it was easier to spot EPNCIL as a jumbled word than PENICL.

The bogus neurons processed these words by adding upwardly the responses to individual letters independent within the discussion. They could also predict the time that the human brain would take to correctly identify a non-jumbled word from within a group of jumbled words. This was confirmed past experimental findings.

Finally, the researchers used functional MRI to capture brain images of volunteers performing a word recognition job to run across which region of the brain got activated during the process. They found that observing a word activates the lateral occipital region – the part of the brain that processes visual information. Post-obit this, the brain compares it with similar-looking words, which is probably stored in the visual give-and-take form expanse (VWFA).

"We hope that our model would address the shortcoming of existing models that aim to scissure the orthographic lawmaking and compel researchers to reconsider the contribution of vision in orthographic processing," Agarwal says.

Arpan Banerjee, Additional Professor, National Brain Research Centre (NBRC), who was not involved in the study, says that one unique aspect of this study is how computational modelling has been used to explain the neural data.

The findings could assist in developing efficient text recognition algorithms and also enable amend diagnosis of reading disorders similar dyslexia. "It would be interesting to run into how this model can work for more complex languages like Hindi and Urdu," Banerjee says. He also wonders if the properties of the artificial neurons would change afterward learning two languages.

The team intends to explore the part of visual processing in predicting reading fluency in children. "While deficits in phonological processing are the primary cause for dyslexia, a subset of children has deficits at the visual level. We aim to identify this subset through visual experiments and develop training regimes to help improve their reading fluency in our adjacent follow-up study," Agarwal says.

Source: https://indiabioscience.org/news/2020/a-new-study-explains-how-the-human-brain-recognizes-jumbled-words

0 Response to "What Part of the Brain Reads Words"

Post a Comment